An Eye for Colour, A Feel for Cloth

A feature on Tricia Guild and the early years of Designers Guild

Before the name became a shorthand for painterly colour and bold florals, before the showrooms and glossy pages, Tricia Guild began with cloth. Not flashy or fine, but block-printed Indian cottons, handmade, sun-warmed, and imperfect in all the right ways. They spoke to something quiet and essential. Texture. Craft. Place. That’s where the story begins.

The early interiors were a collage of sorts. A gentle rebellion against the hard-edged patterns of the 60s and the polished conformity of established taste. Think cane chairs, coir mats, patchwork cloths, beaded lamps. Ceramics beside paintings beside handprinted wallpaper. It wasn’t eclectic for the sake of it, it was just what felt right.

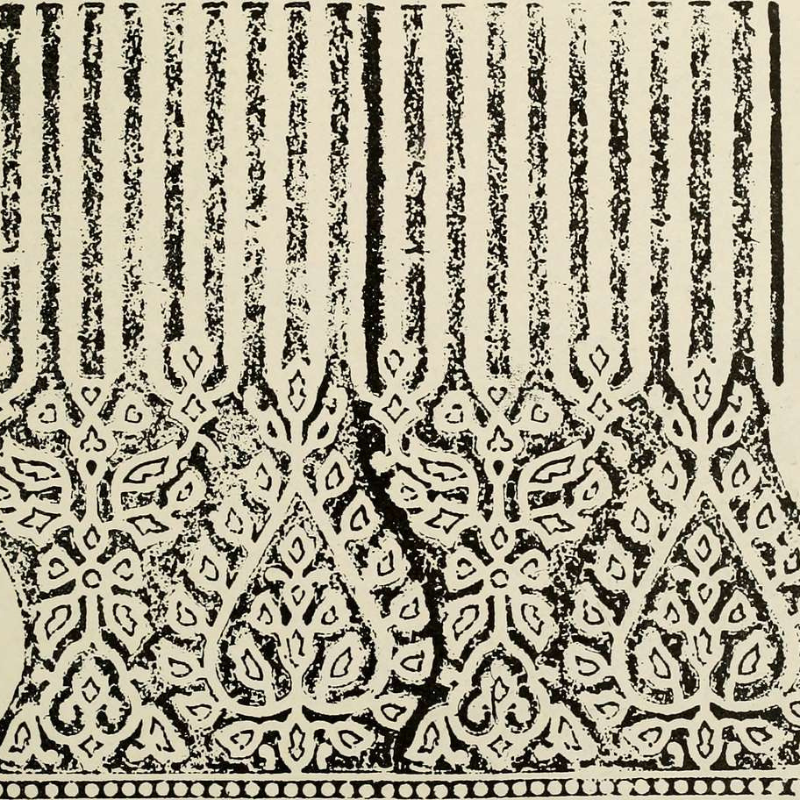

Indian block print, c.1924. The kind of rhythmic pattern and softened geometry that first caught Guild’s eye.

Where Heal’s was offering geometric primaries and Sanderson played in florals, chintzes and Japanese wallcoverings, Guild did something else entirely. The Village prints, small-scale and richly coloured, offered a new kind of language. They were designed to mix, not match. To build a story, not fill a room. And perhaps that’s what unsettled the establishment most. No rules. Just intuition.

By the mid-70s, colour was becoming bolder. And so were the collaborations. Kaffe Fassett’s Geranium (1975) was exuberant and wild. Moodboards were pinned, room sets styled, collections shown at the London Design Centre like painterly vignettes of a life well lived.

Geranium woodcut, 1916, an early 20th-century interpretation of a form later reimagined by Kaffe Fassett for Designers Guild. The same bold bloom, held in graphic harmony.

There were other collaborations too. Lillian Delevoryas brought her painterly calm to cloth in the late 70s. Ceramicist Janice Tchalenko and printmaker Howard Hodgkin followed in the 80s. And then came Grandiflora, loose, watercolour-like, blooming across fabric in 1987 like a botanical dream.

Designers Guild was no longer just a fabric house. It was a point of view.

“A home built through fragments, through feeling”

A mood-board in motion.

A quiet corner, patterned and personal — the kind of space built by instinct, not instruction.

Photograph by Juliane Monari via Unsplash

In 1981, Harpers & Queen described the Designers Guild customer as a cross between New Romantic and First-Homer. Broke-but-in-love-with-home. Sloane Rangers who’d rather make a room their own than follow a trend. The sort of people who stitched things together from memory, from mood, from market finds.

The kind of people who’d feel right at home in Tricia’s world.

Listen to the Audio Feature

Fragments and Feeling: Tricia Guild & the Craft of Designers Guild